KATIE FOWLIE

current research

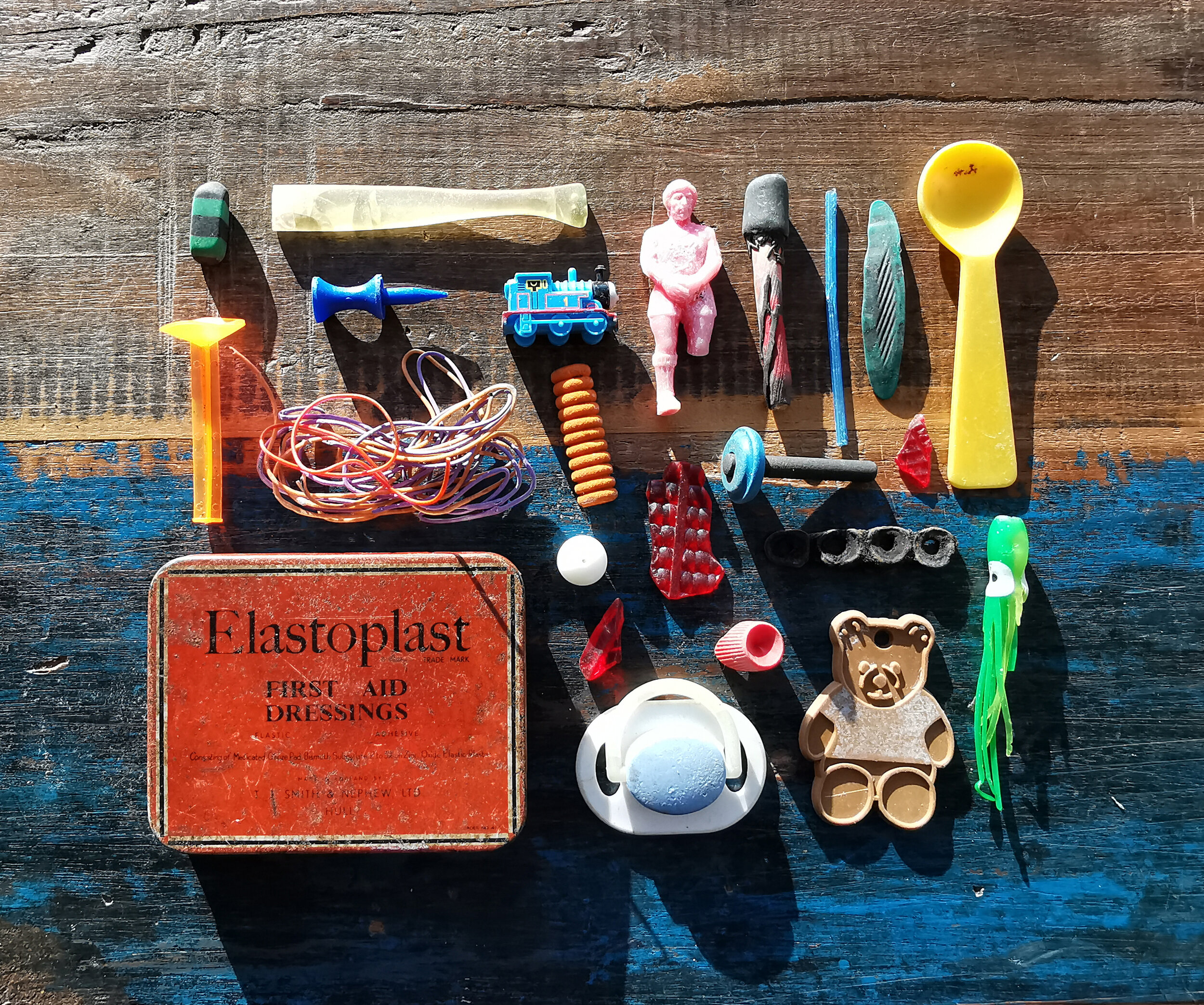

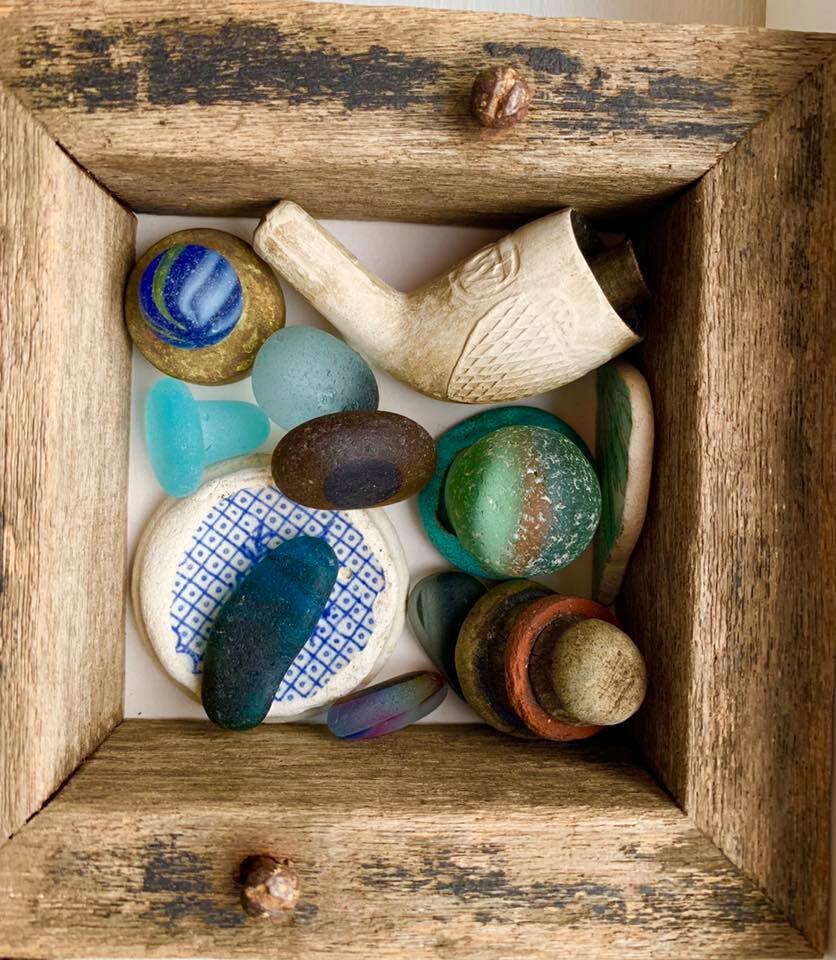

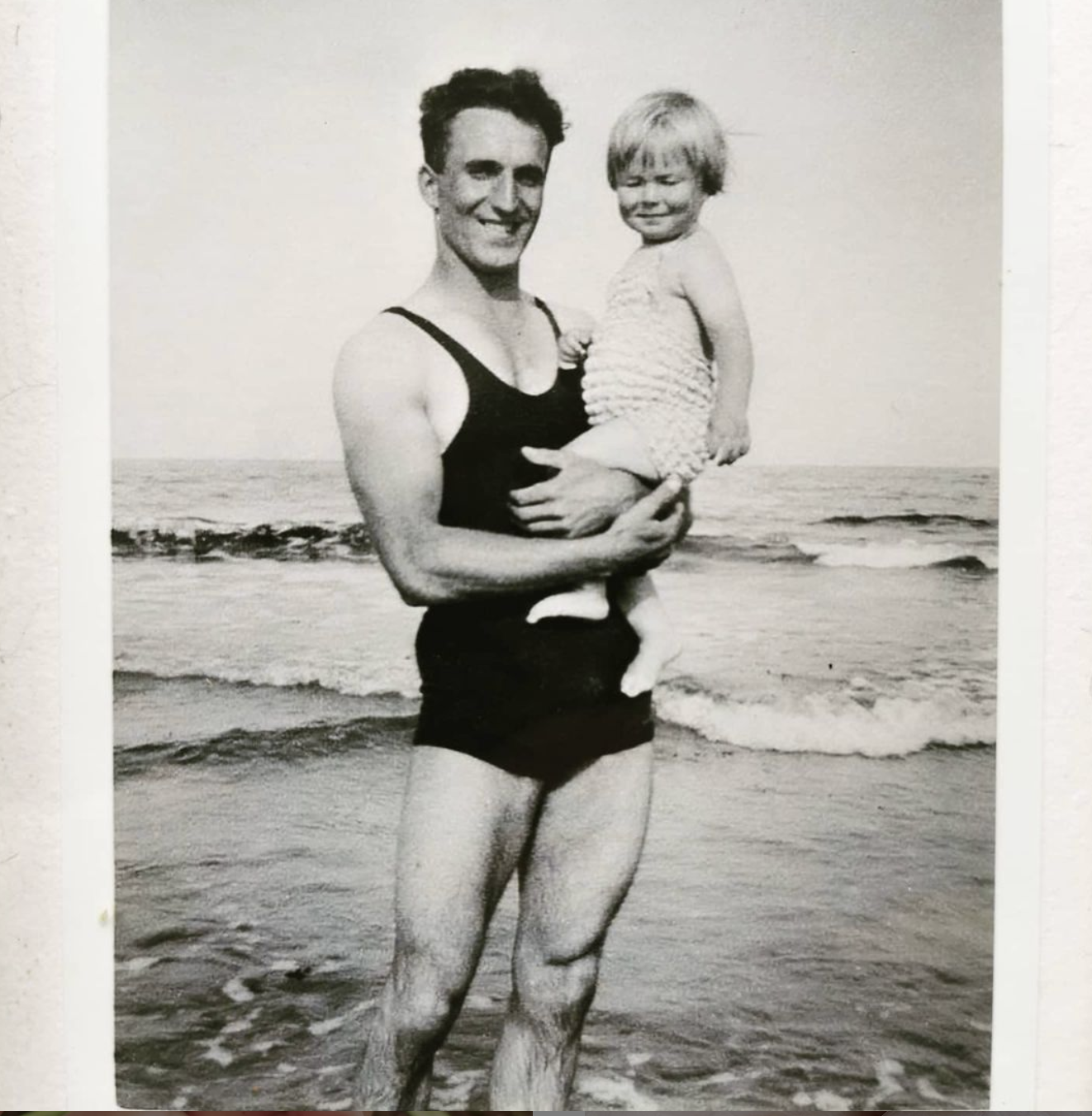

I am a multidisciplinary artist living and working in Fife, in the coastal town of Lundin Links. I was fortunate to grow up on the outskirts of St Andrews, with a mother who instilled in me both a respect for artistic expression and a deep connection to the Scottish landscape and the sea. I walk our coastal landscapes every day looking for man-made sea worn treasures, shaped by their tidal adventures, often spanning 100-200 years. I look for clues in these artefacts to uncover untold stories.

I love the powerful connections that art and heritage can stimulate between people. I get great joy from nurturing this process through work and education. Nature and foraging this coastline for many years has always provided a rich source of stories, old and new, defining our place in the natural world whilst caring for and enriching our environment.

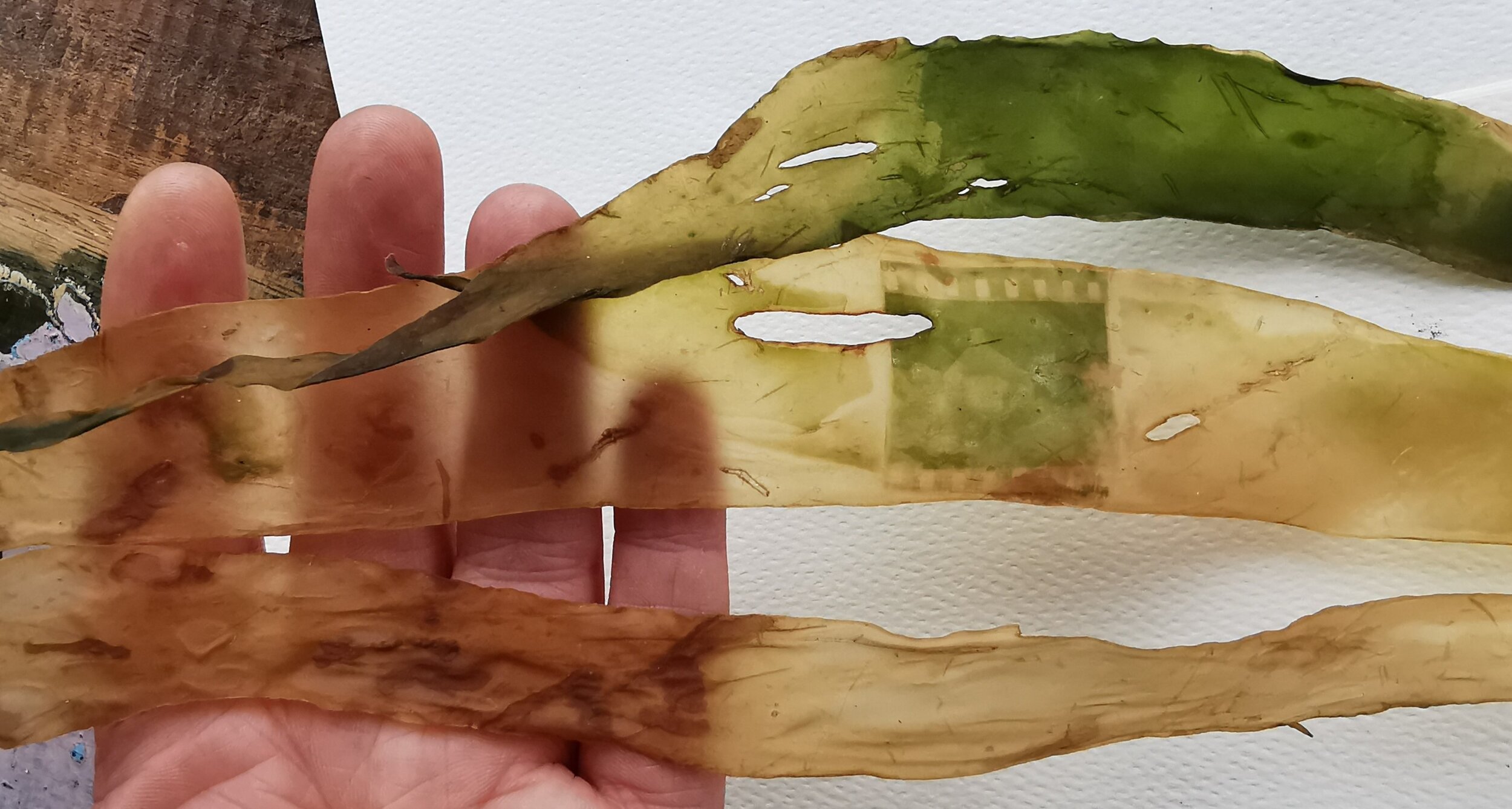

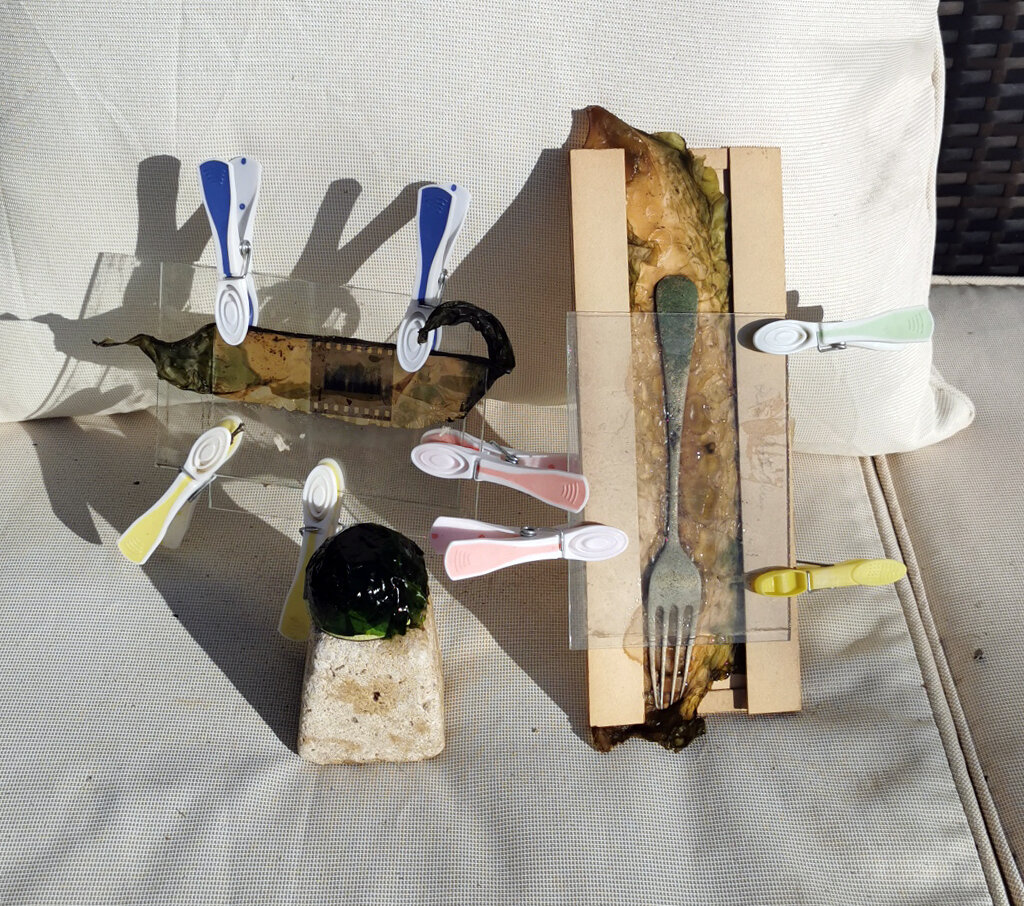

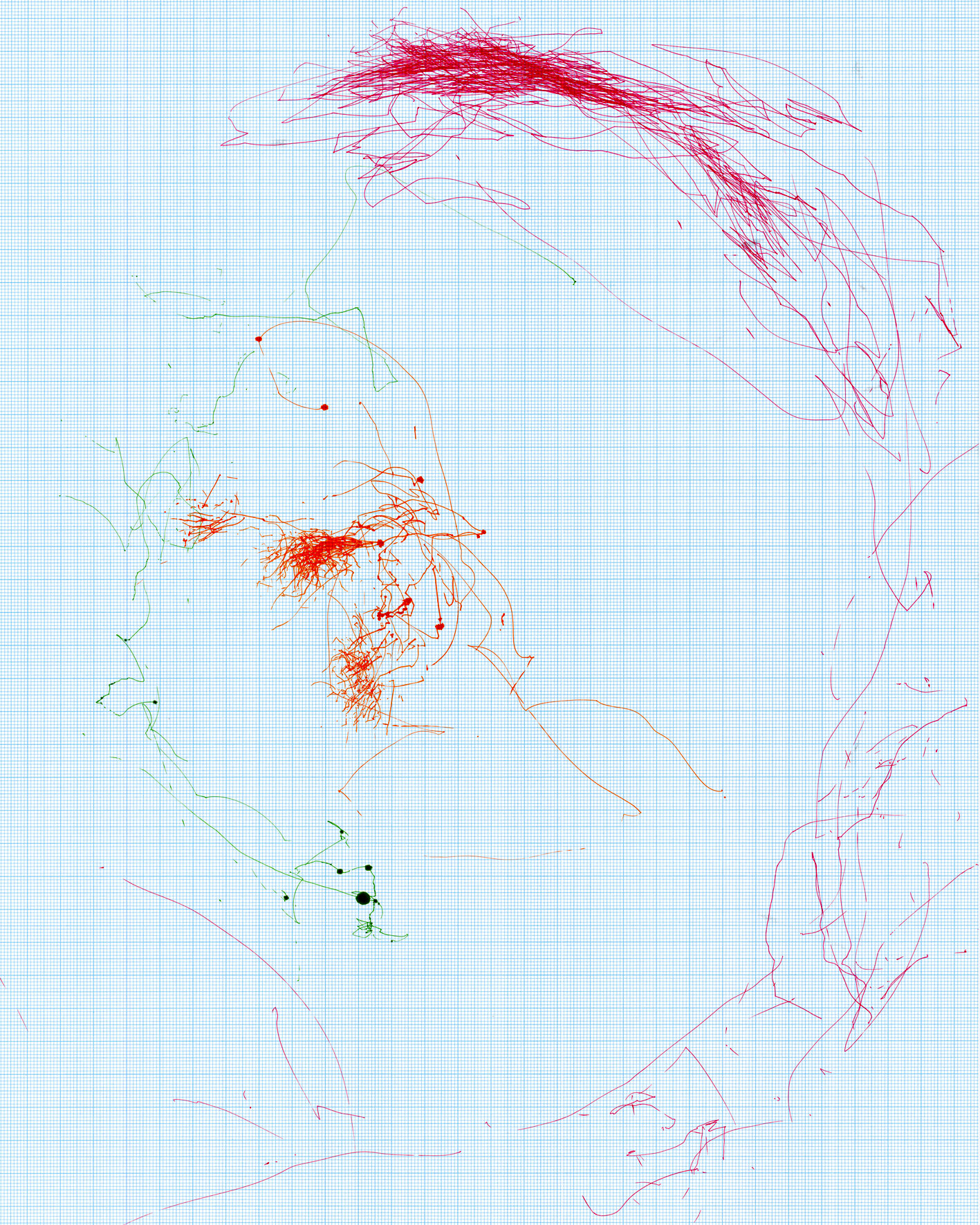

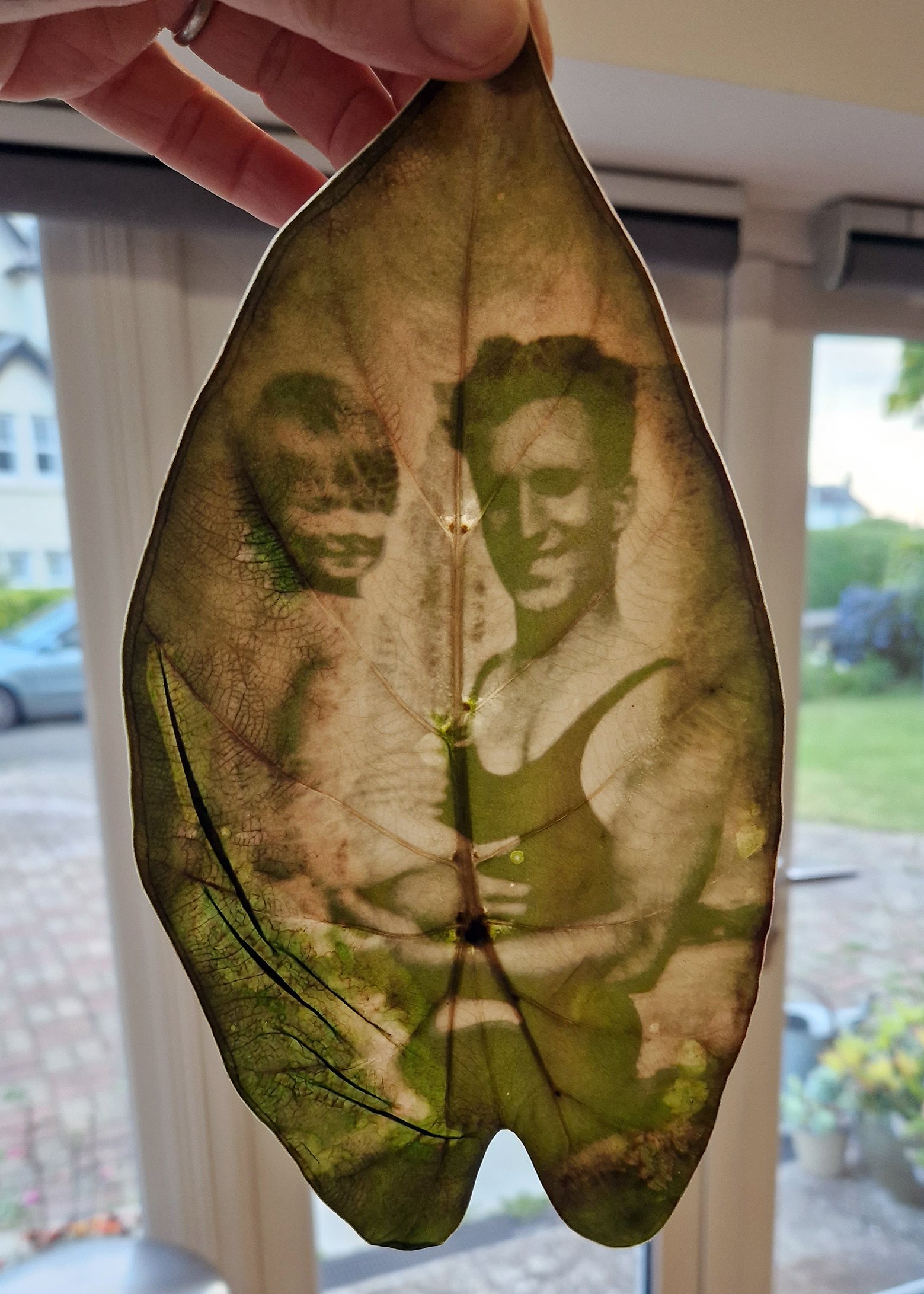

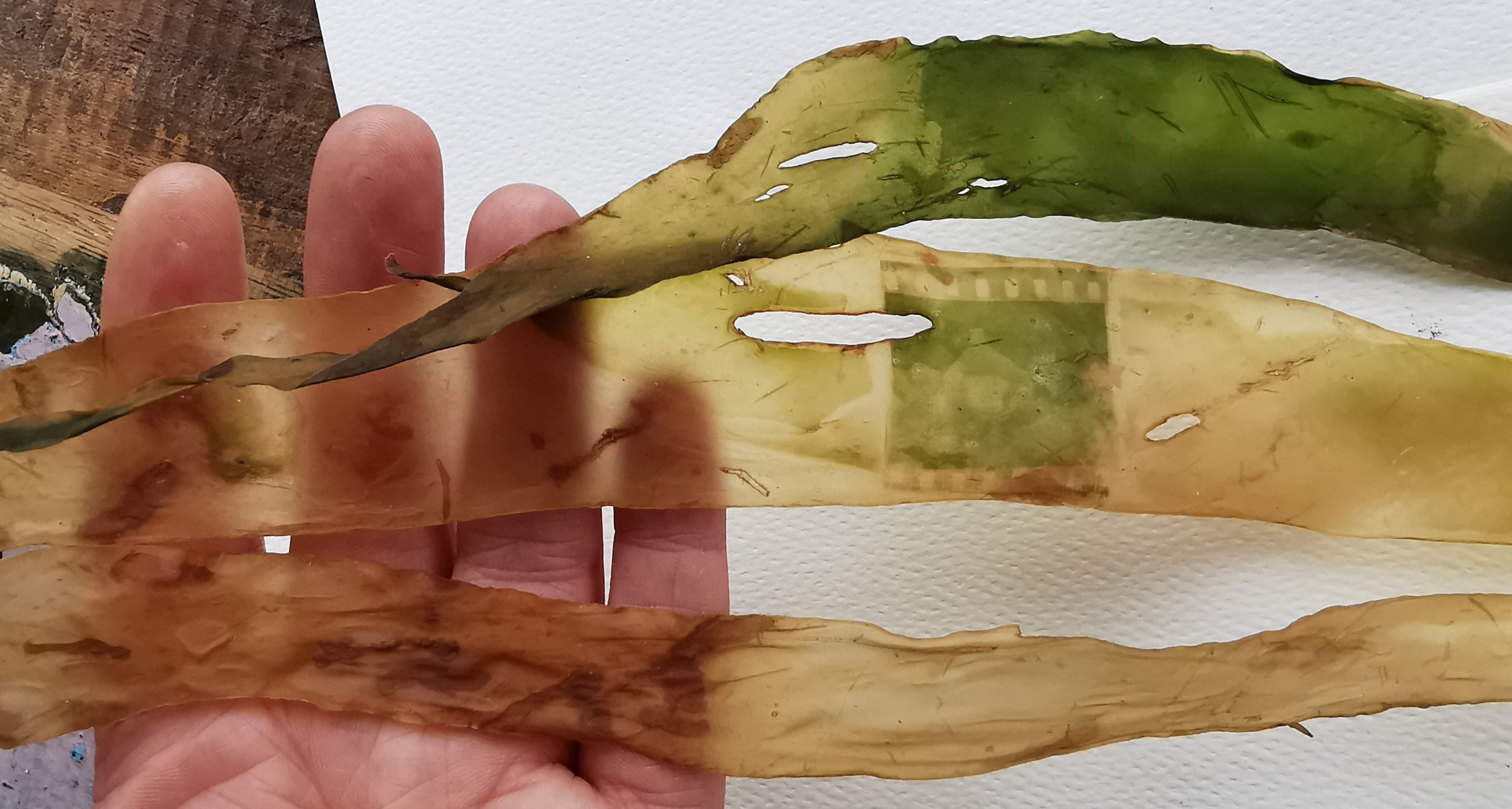

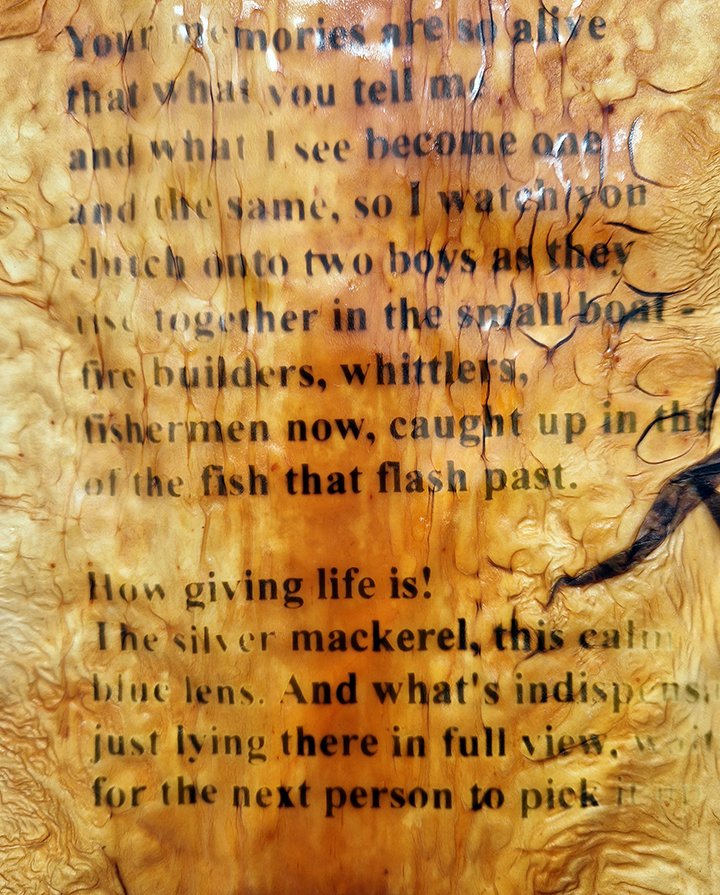

Experiment on Kelp | ‘Indispensable’ | Poem by Tom Pow about my late mother, Jennie Erdal

My inspiration comes from the landscape around me, and foraging has become central to not only my artistic practice, but to the life I’ve carved out as a professional beachcomber & art specialist. Being outdoors each day provides the freedom, sensory nourishment and thinking space to devise creative projects and collect the materials I enjoy working with as an artist. I’m constantly drawn to Fife’s sweeping coastline, its ever-changing landscape and the clues it provides to its Industrial Heritage.

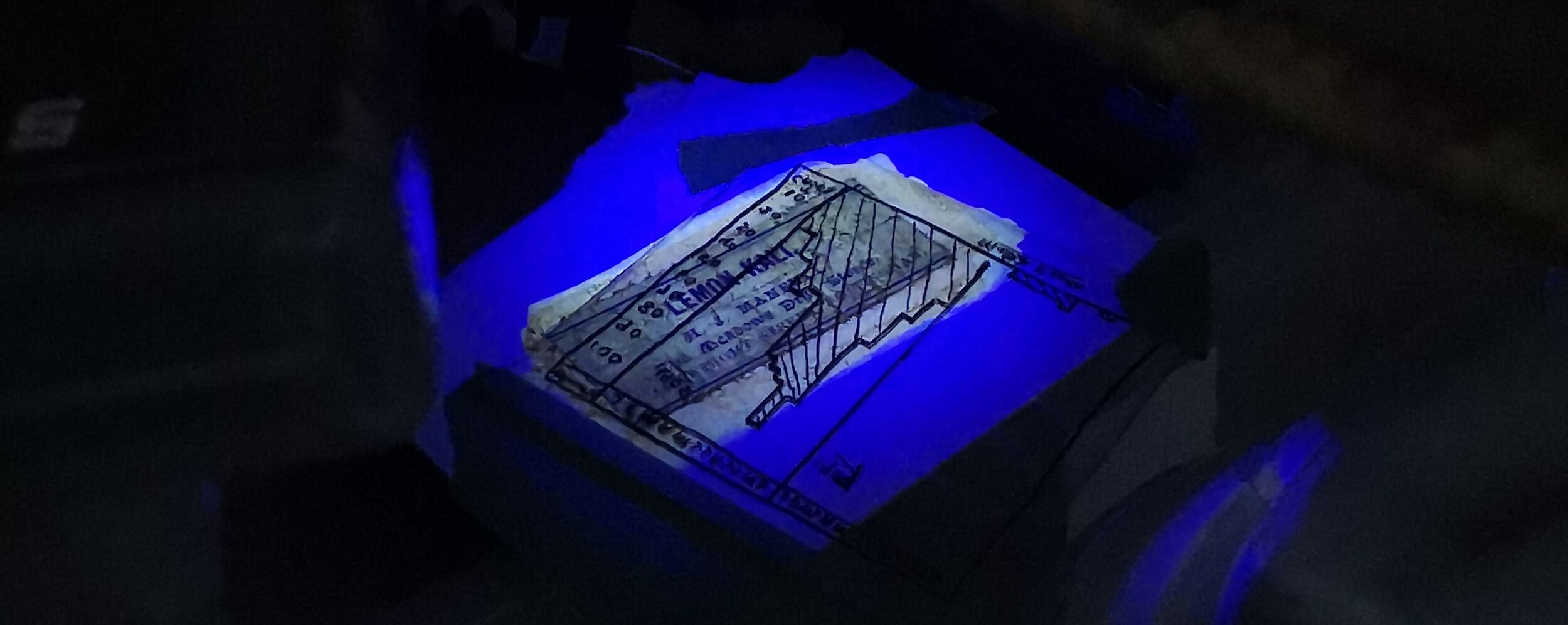

I have a (life-long) obsession with beachcombing and well-developed interests in coastal landscape, foraging, 18th/19th century history, and alternative photography techniques from this era. My various personal and professional interests have led to a sound knowledge of local heritage, industrial, social and economic history during the 18th/19th centuries.

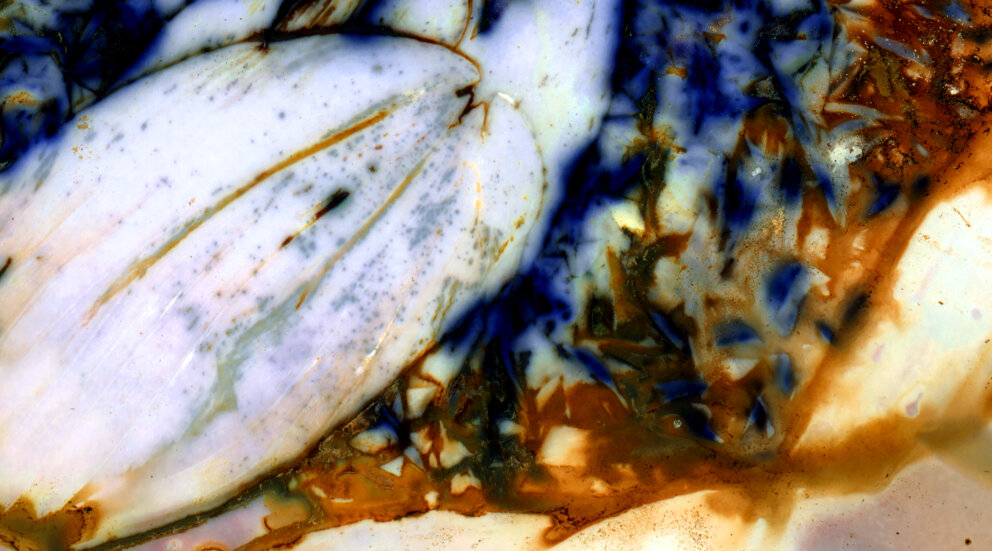

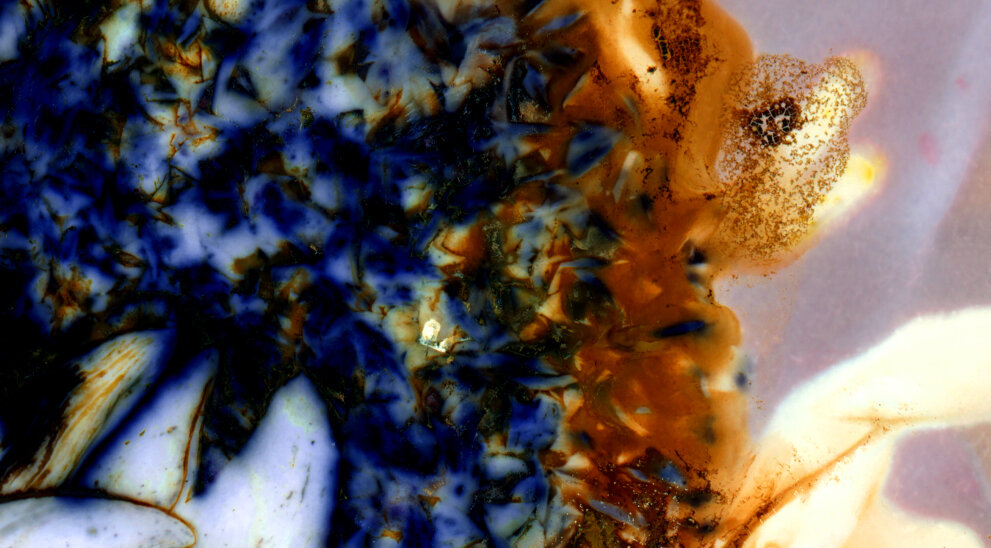

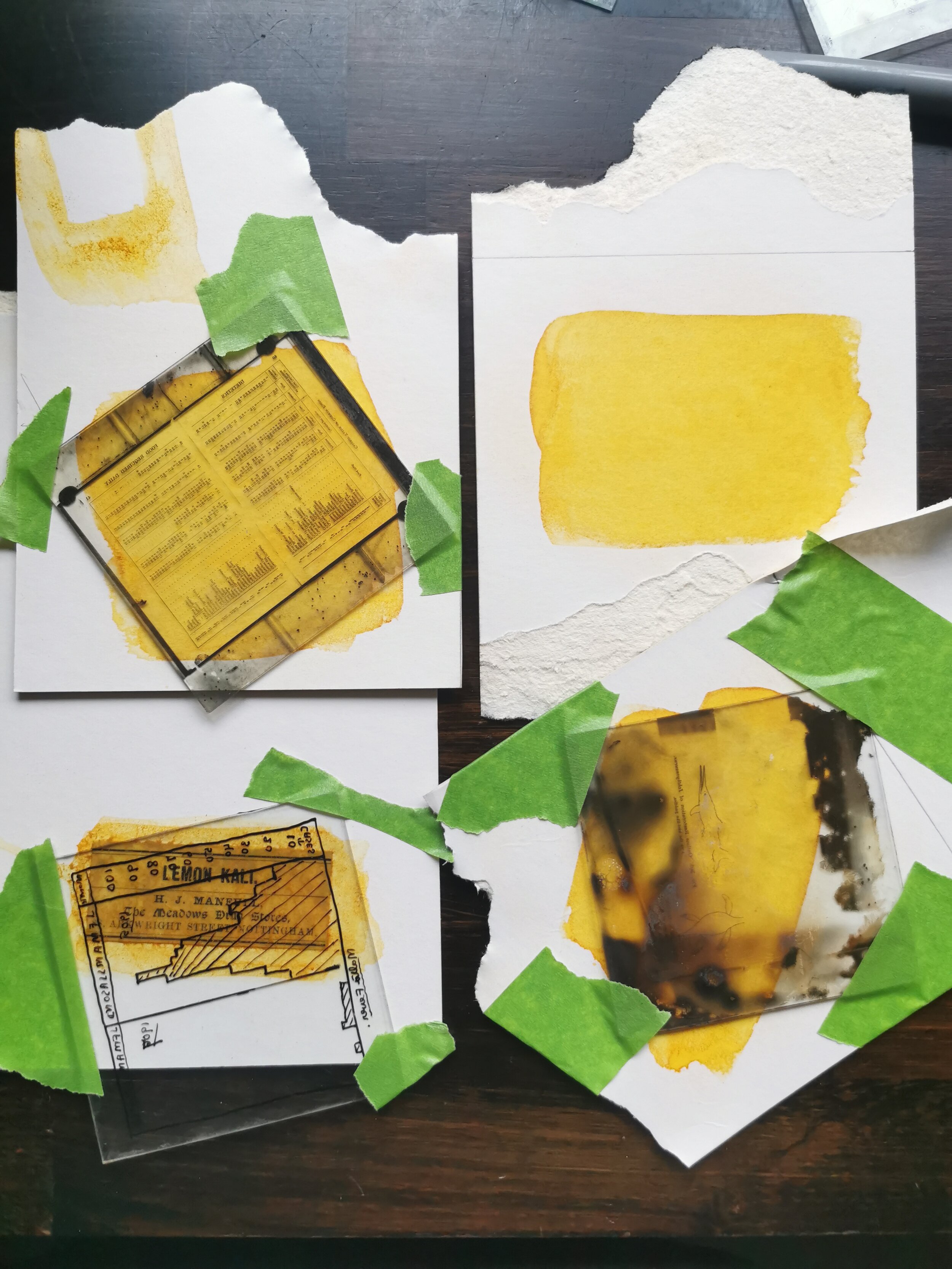

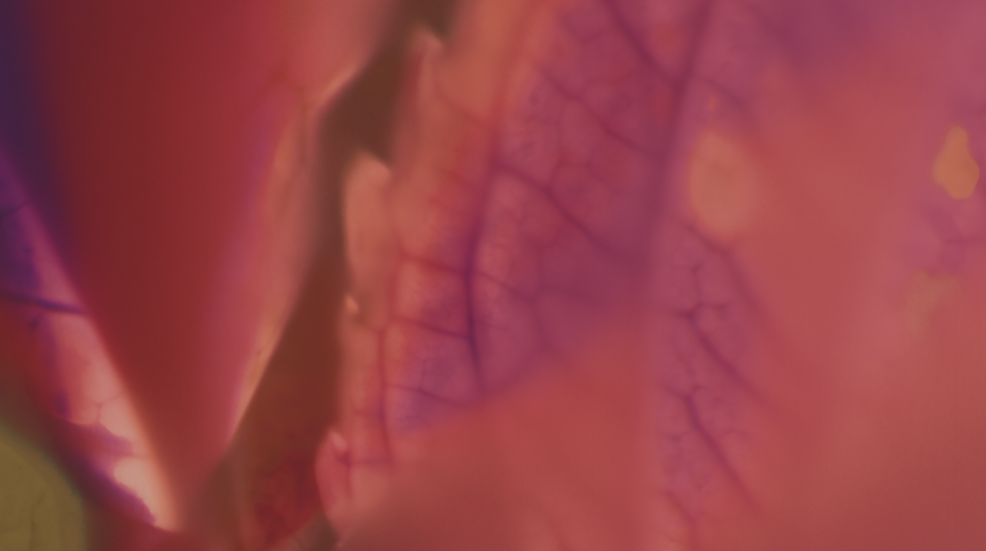

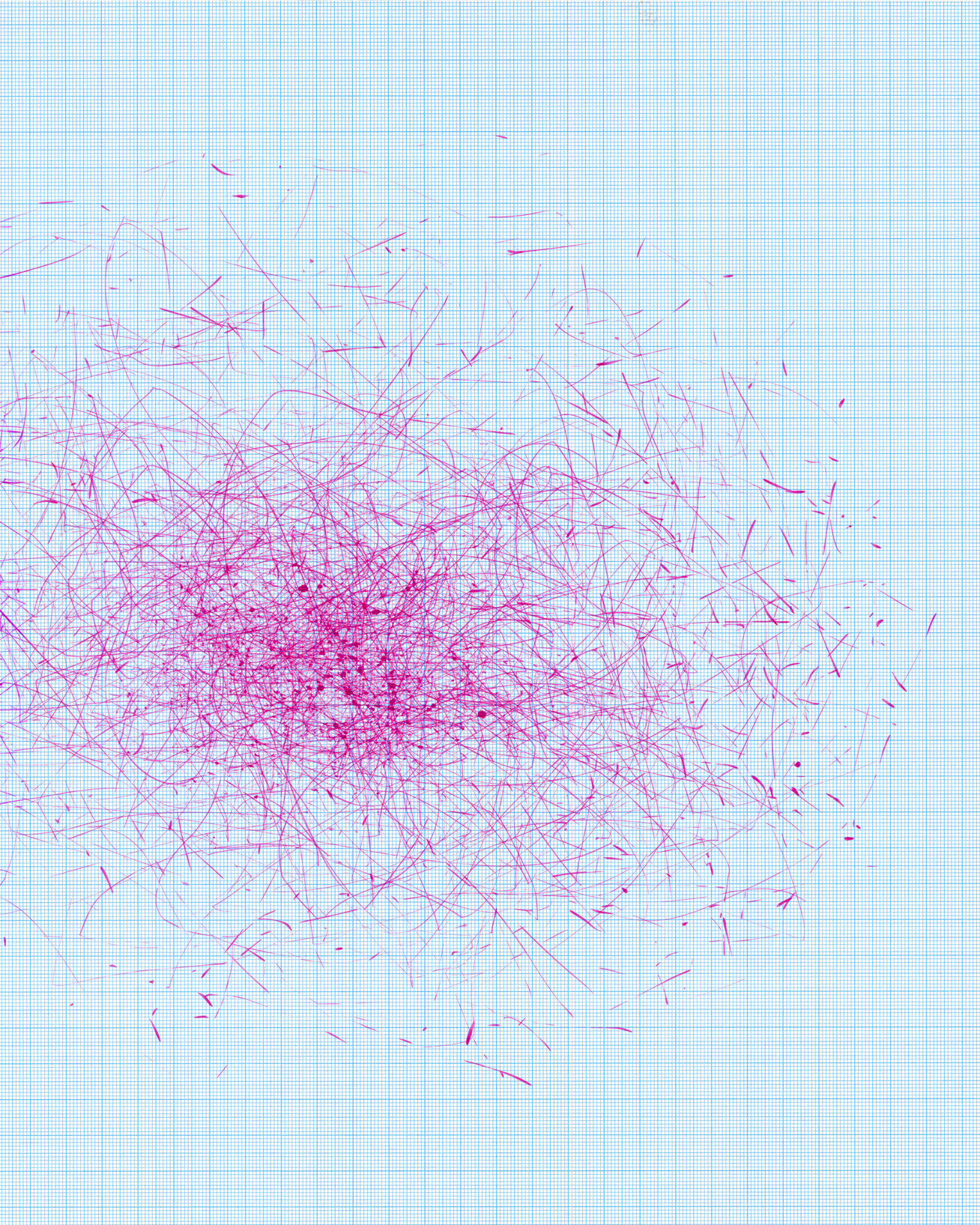

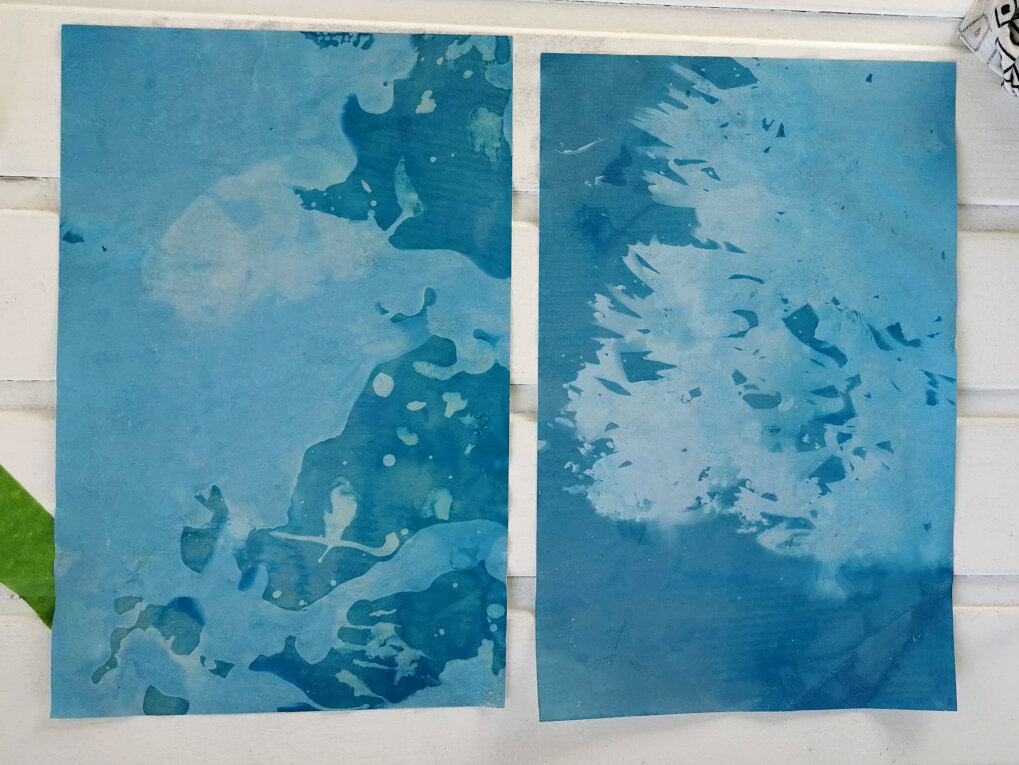

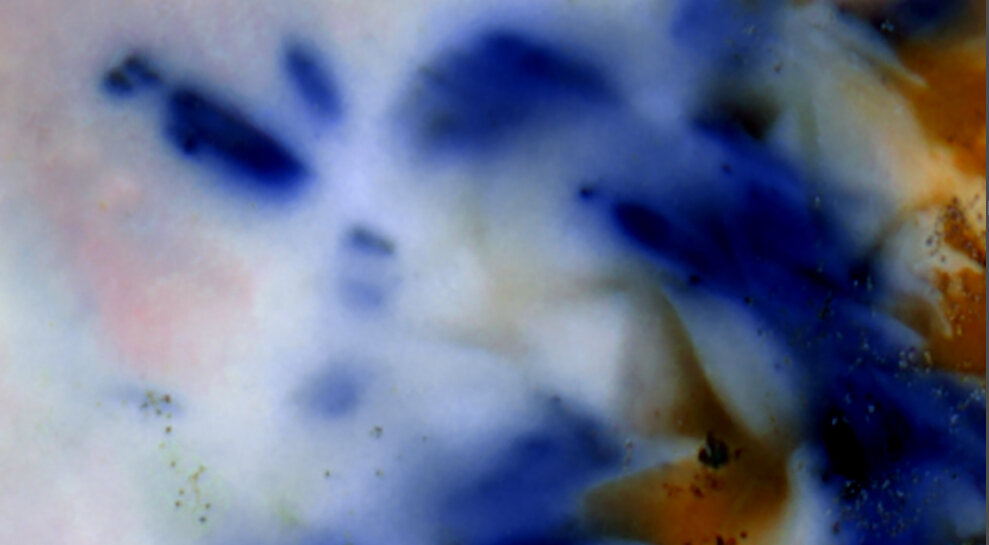

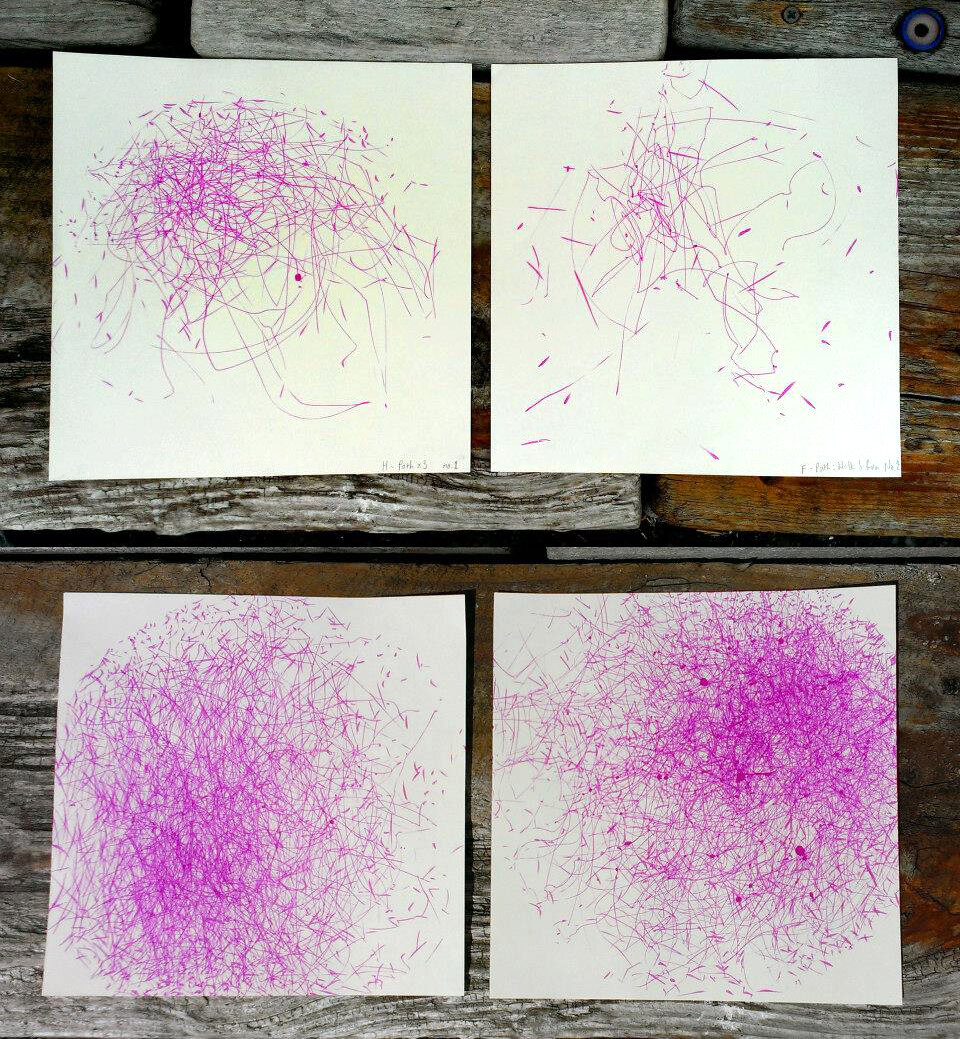

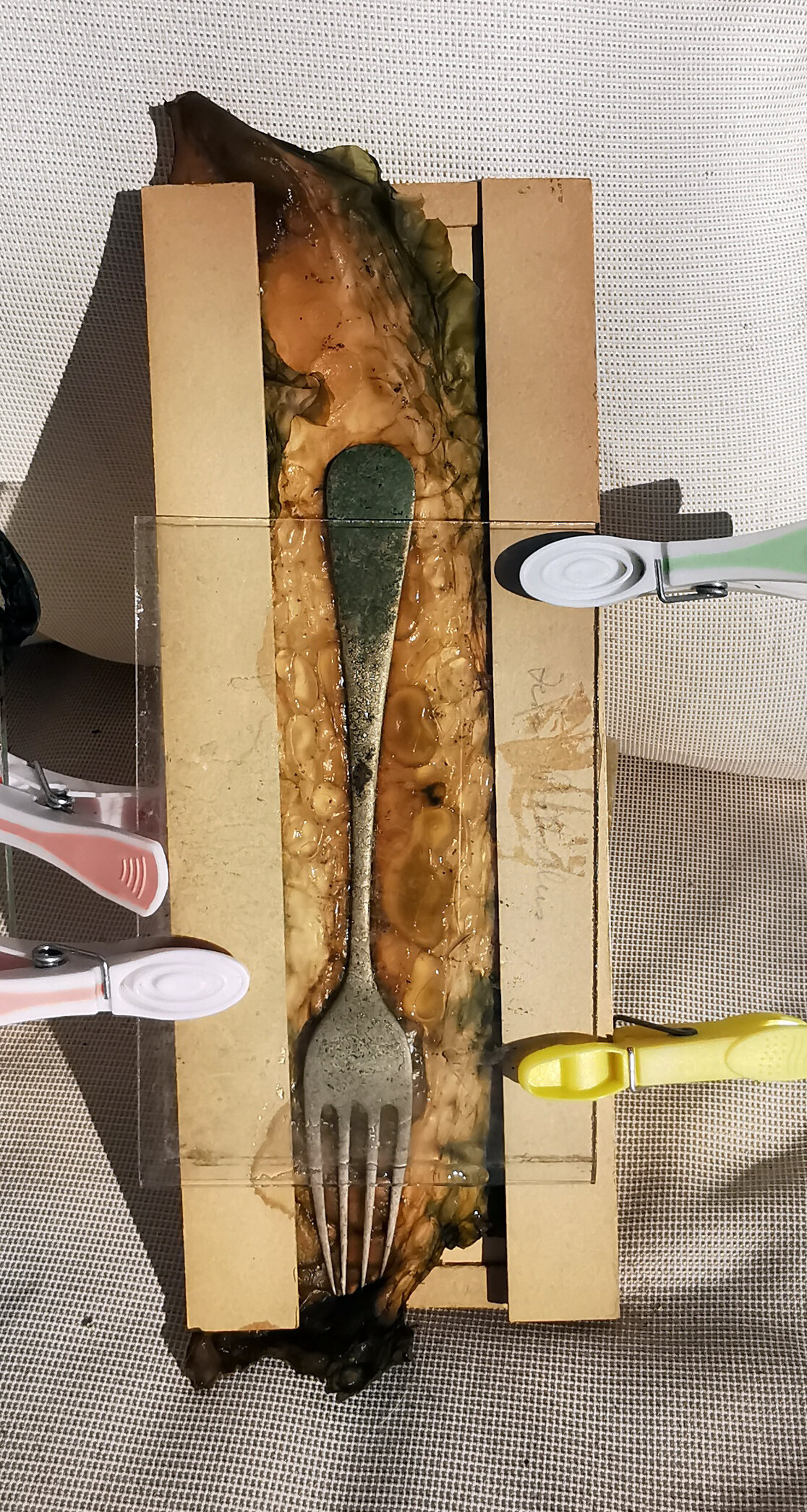

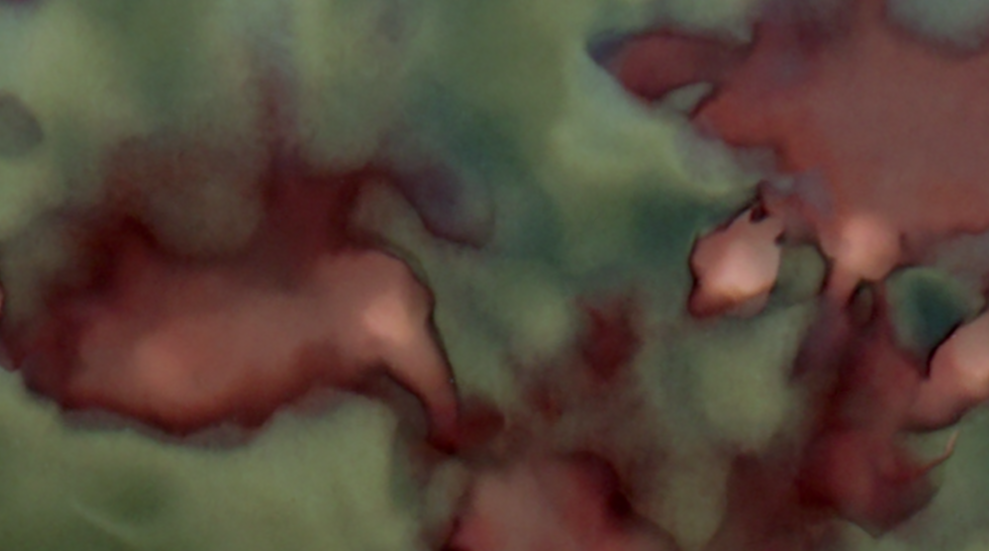

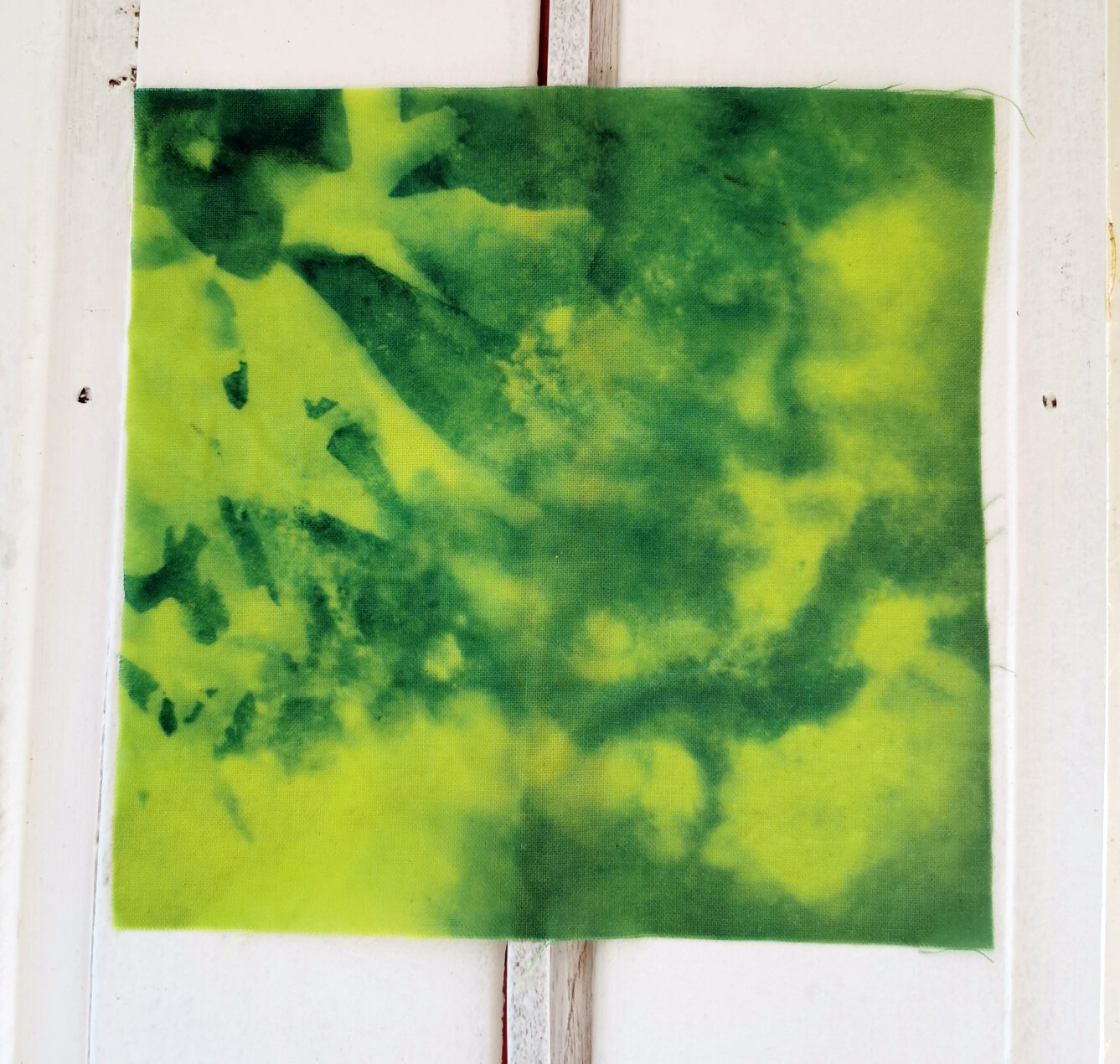

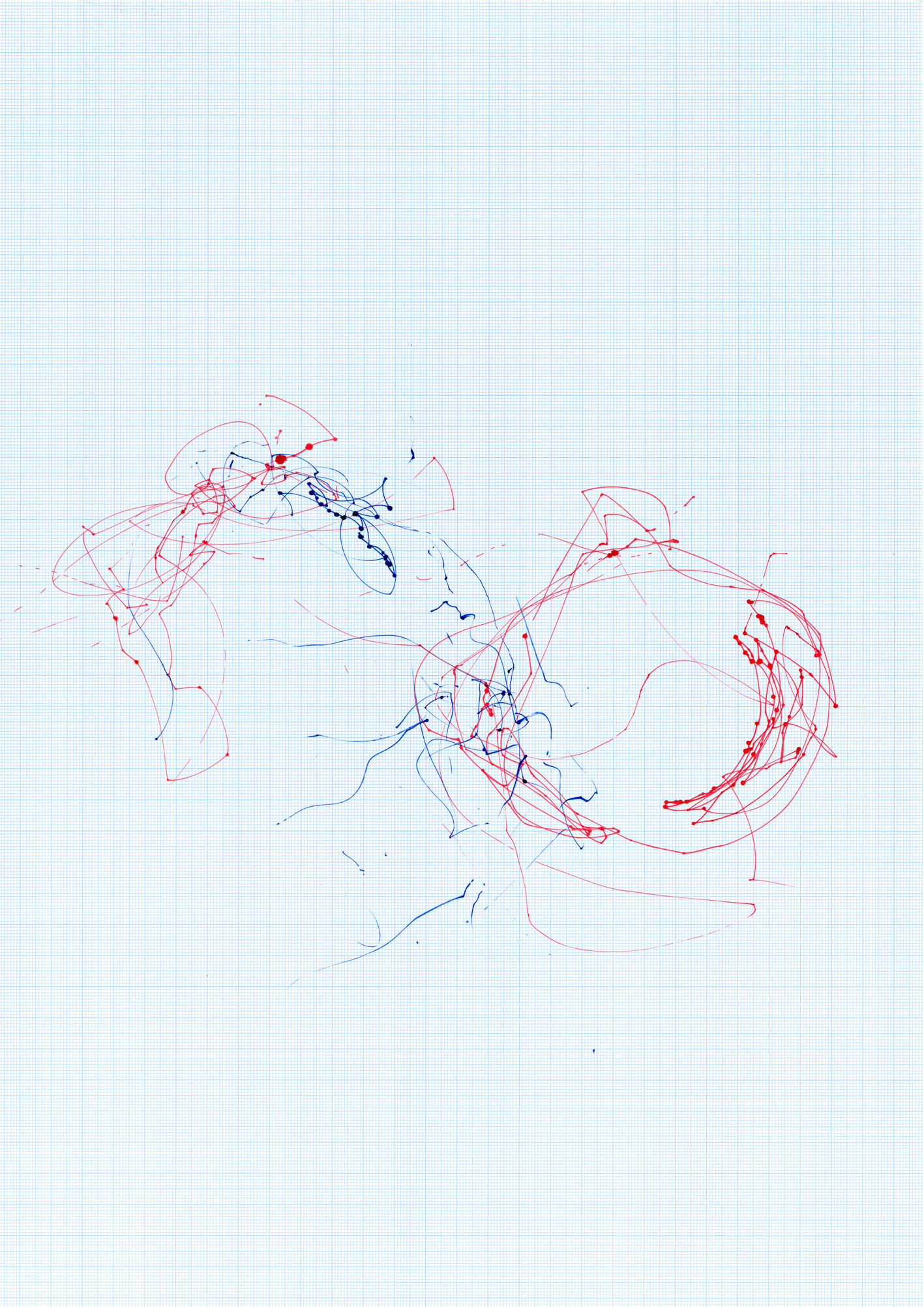

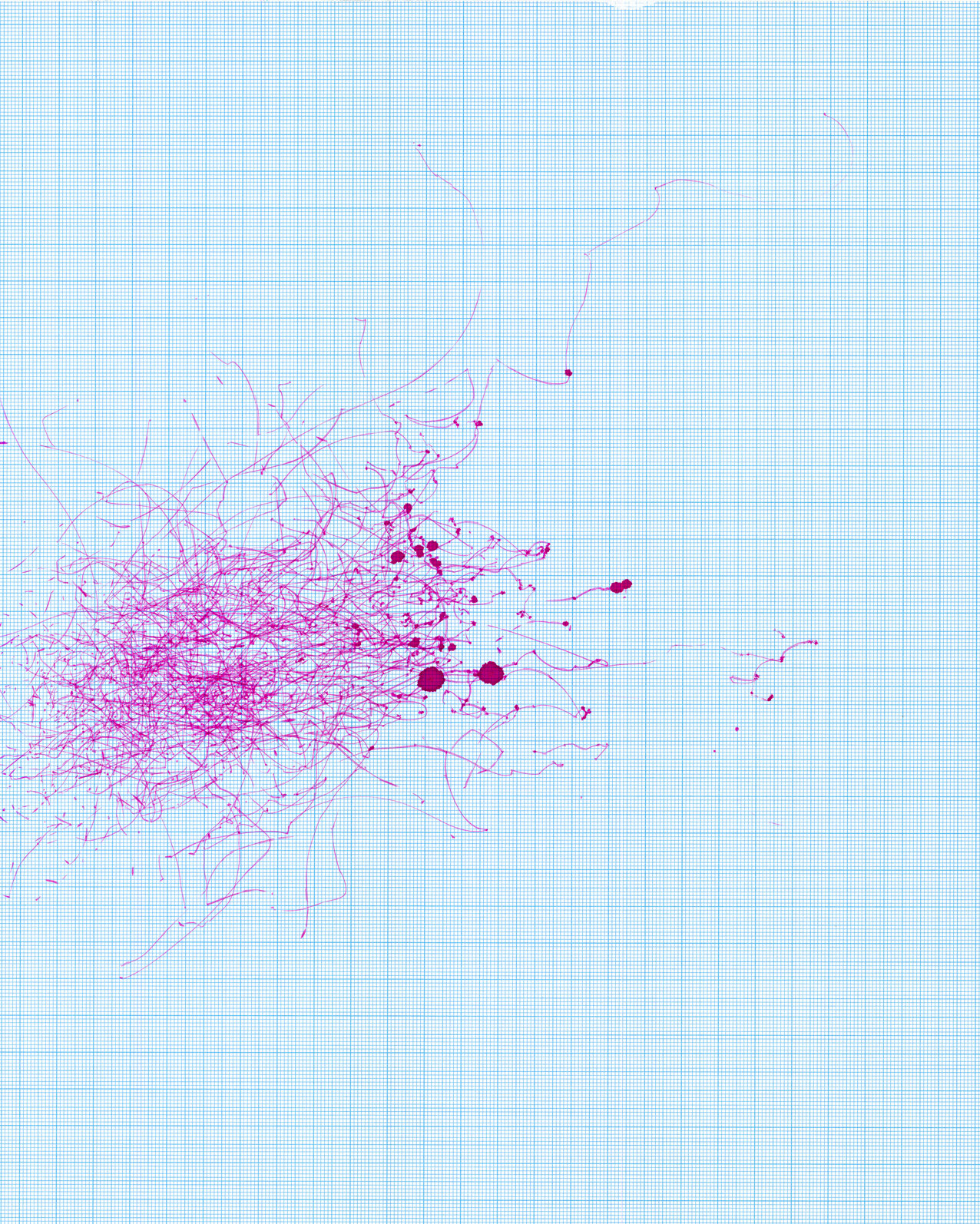

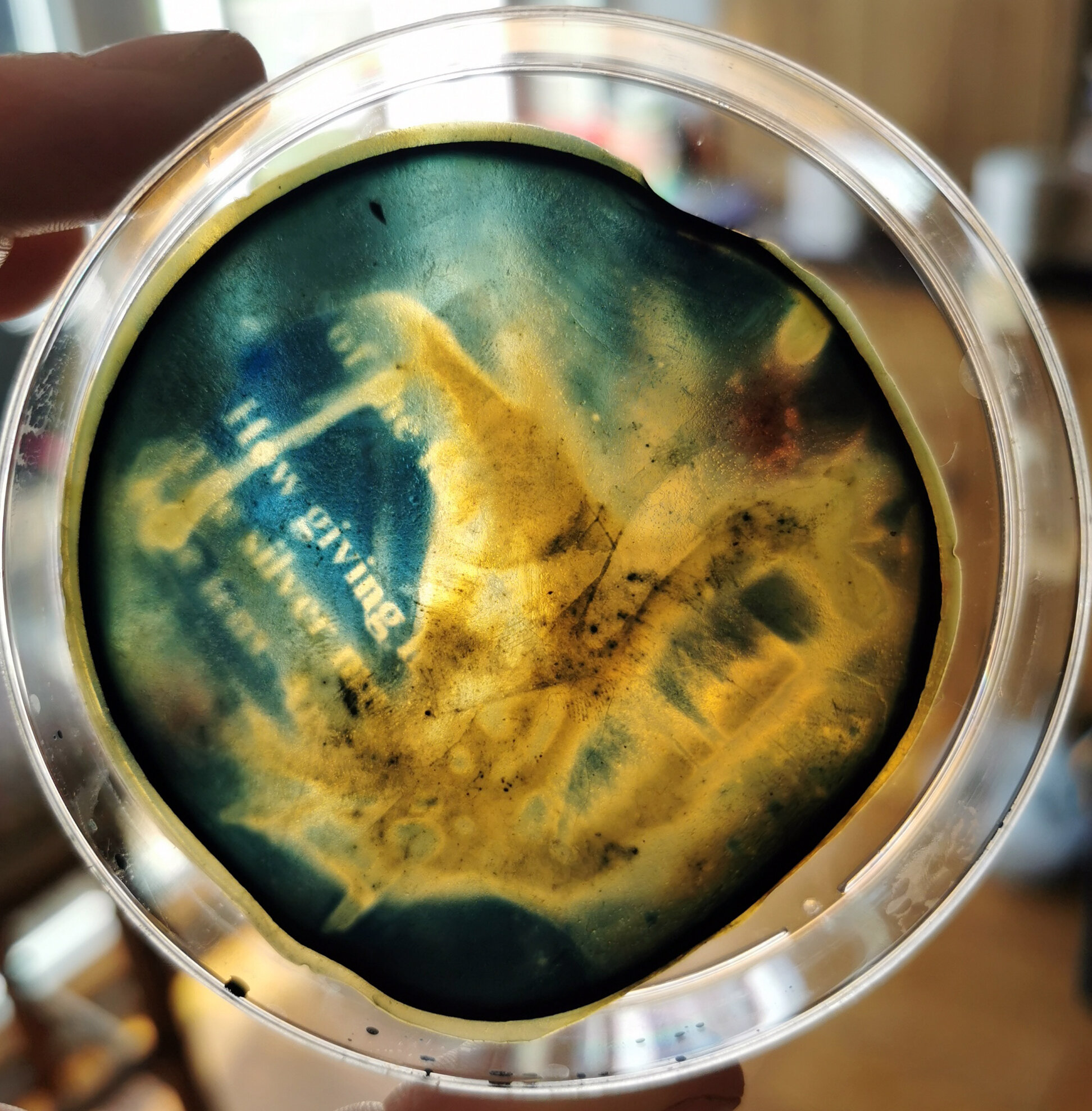

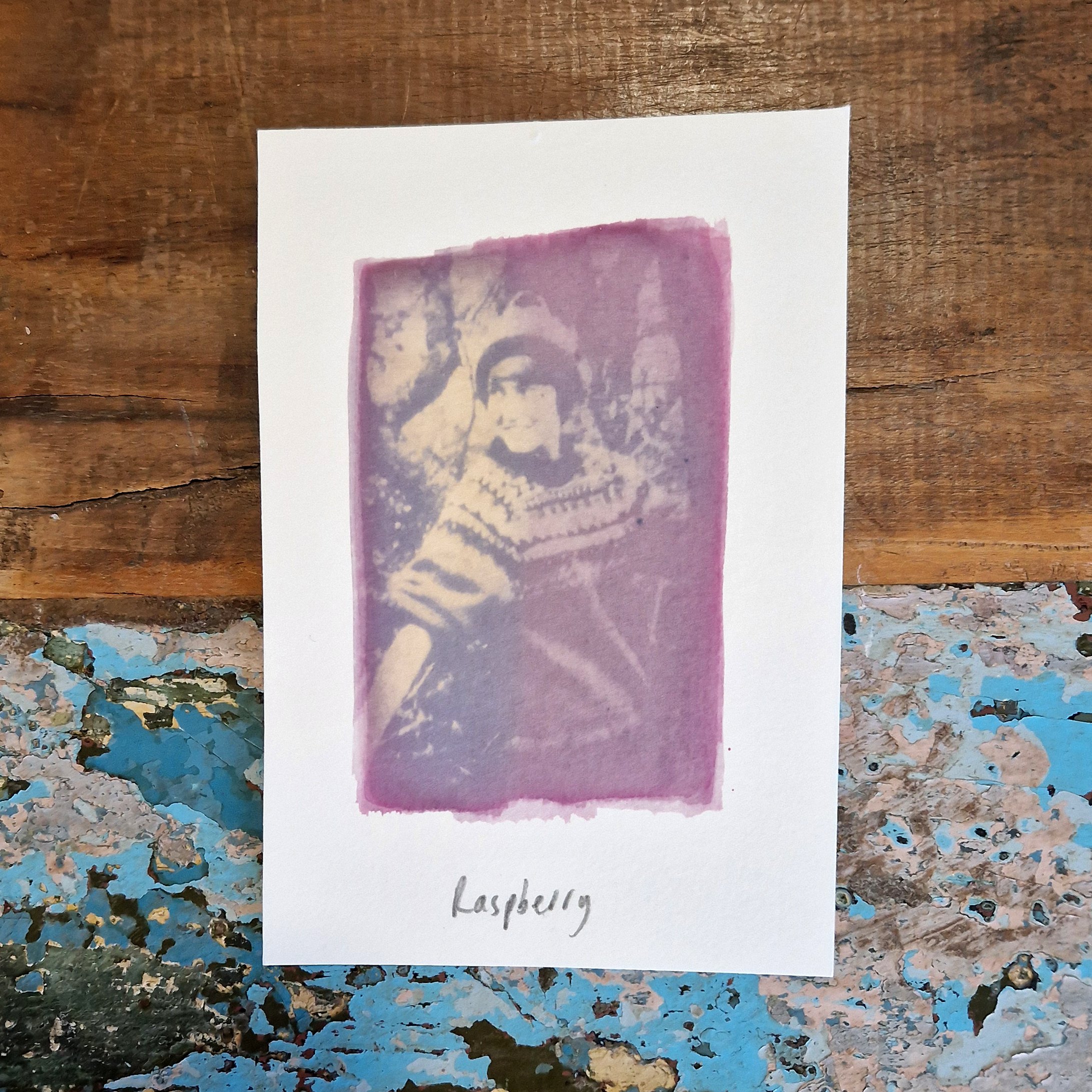

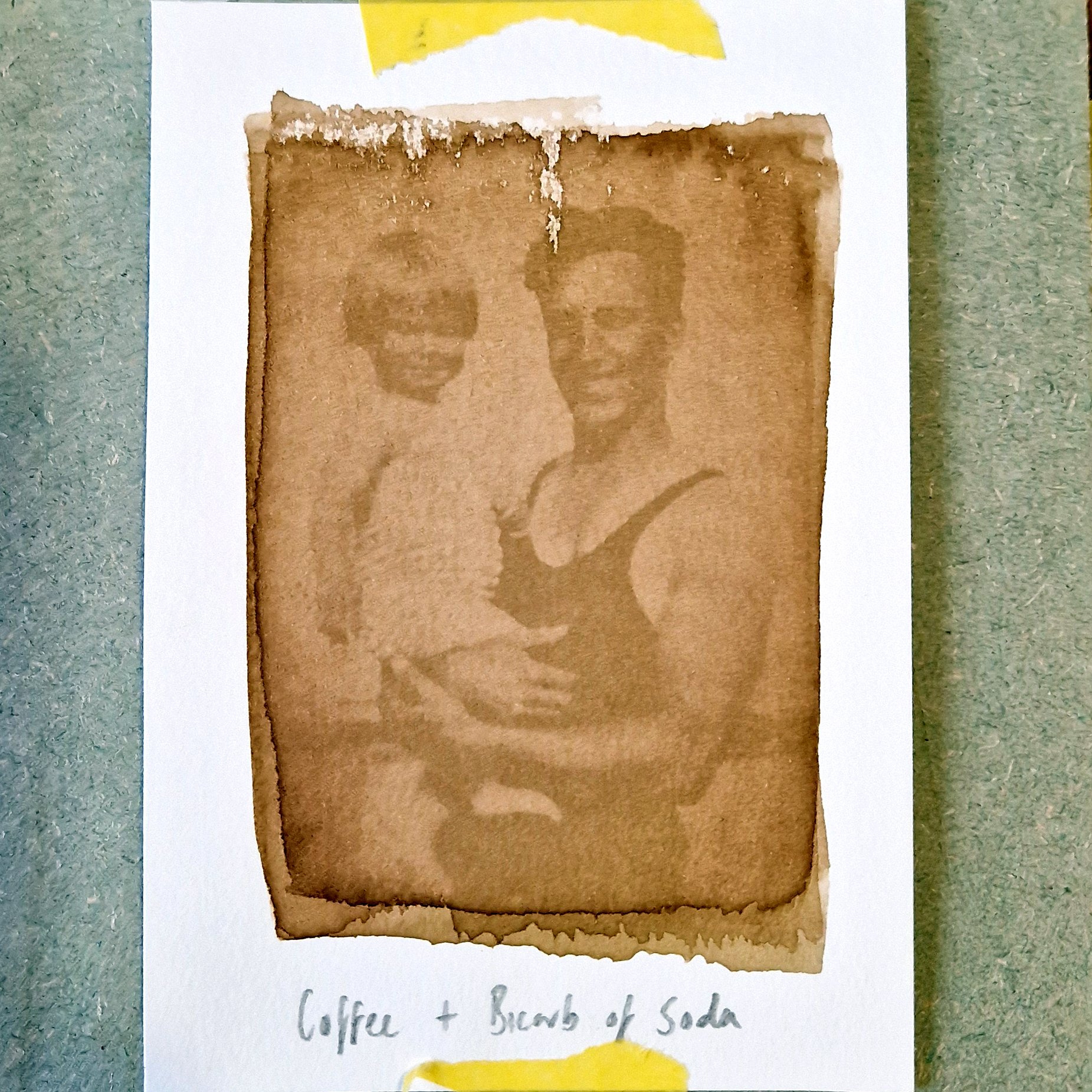

I’m very interested in the photosensitive properties of plants and seaweed, specifically Kelp, as a medium to illustrate its role in our socioeconomic history, how it’s shaped our landscape, and how it could mitigate our perilous future. My current interest lies in applying my knowledge of the Anthotype and Chlorophyll photography processes to seaweed in ways that support this narrative.

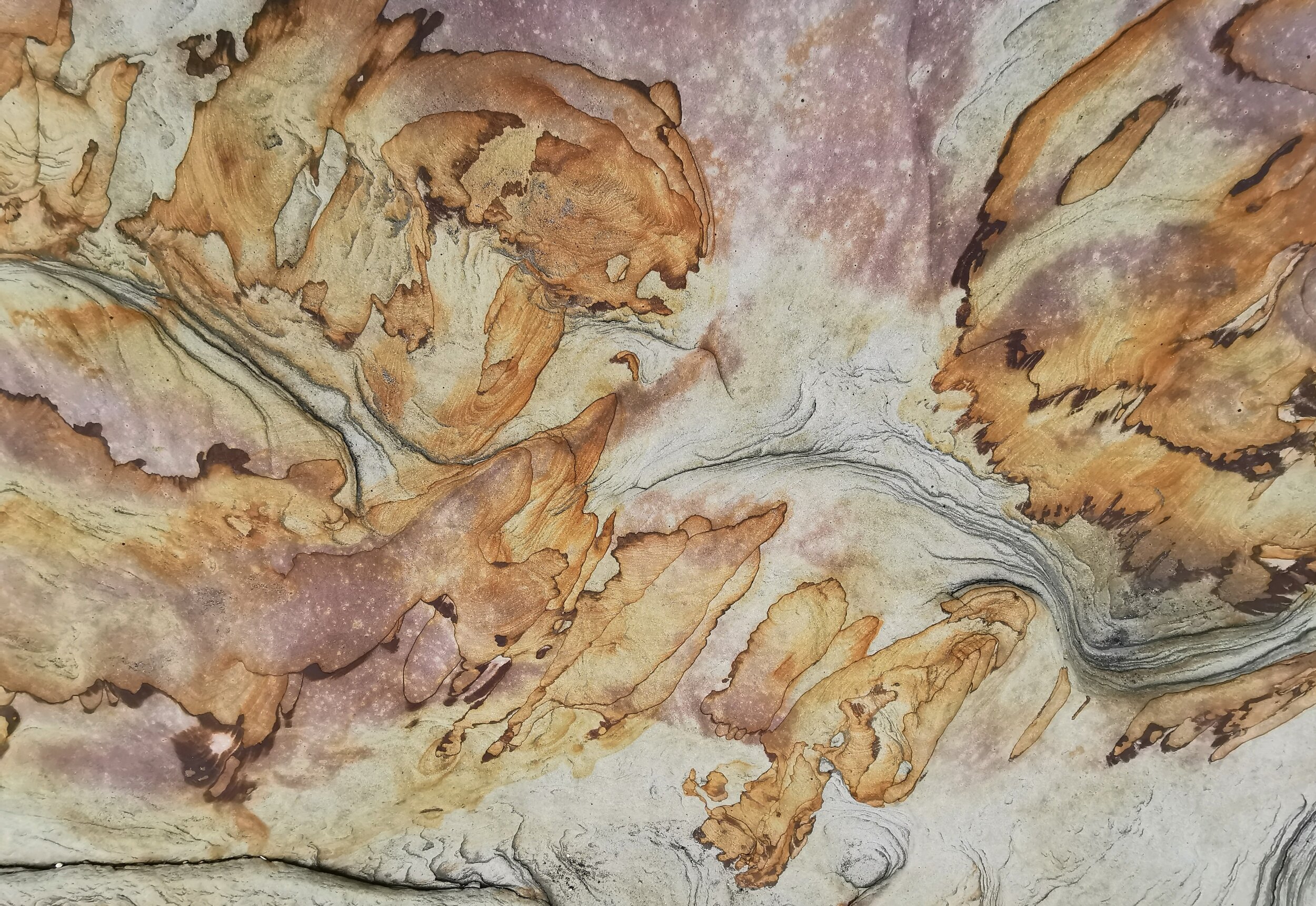

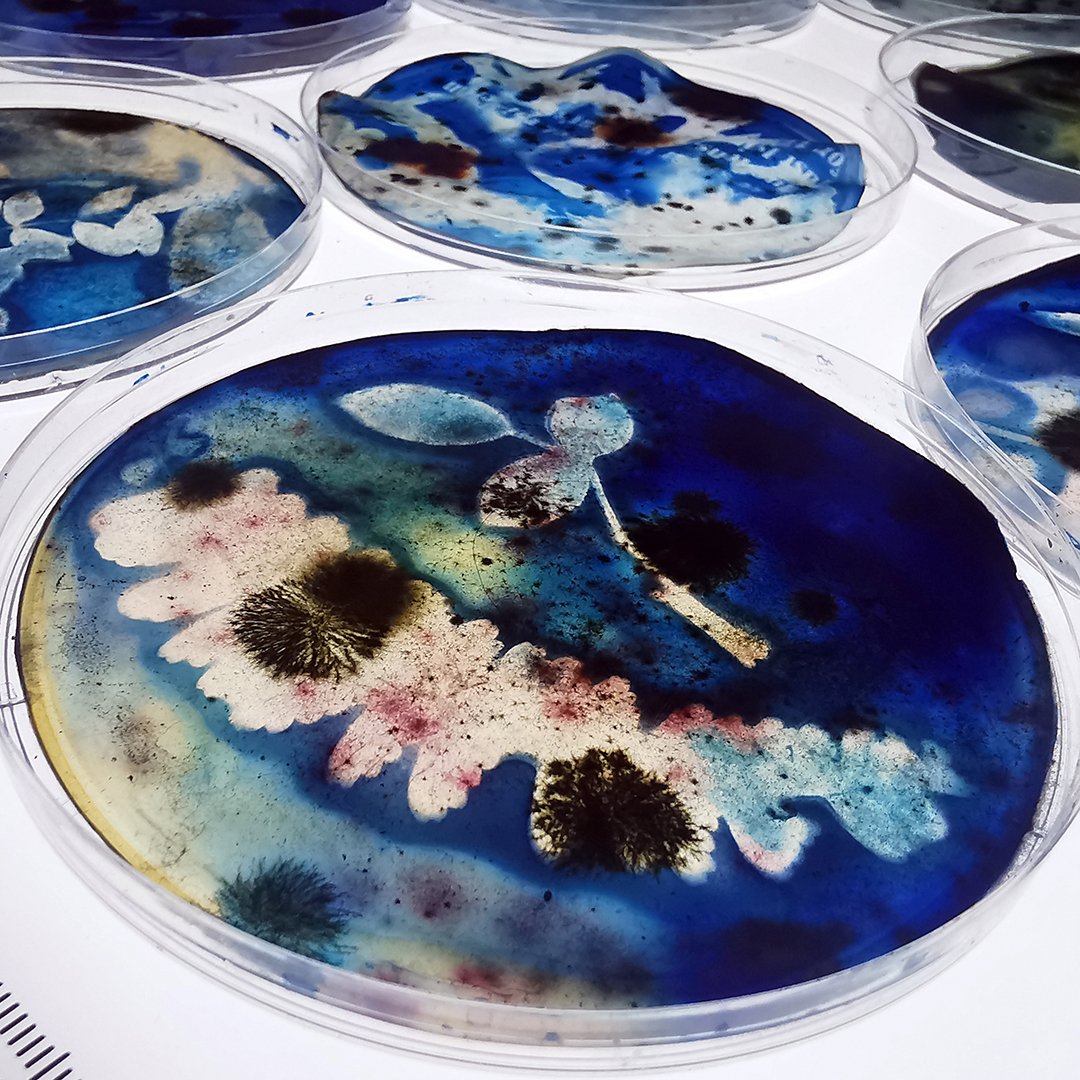

I’m drawn to the impermanence of natural materials, the shift in our need to possess things, and exploring processes which involve the passage of time in their creation. Slow Photography, sometimes referred to as Living Photography greatly interests me, and the opportunities to play with the living and degrading elements and processes involved with plant based photography, especially when incorporating algae and/or yeast.

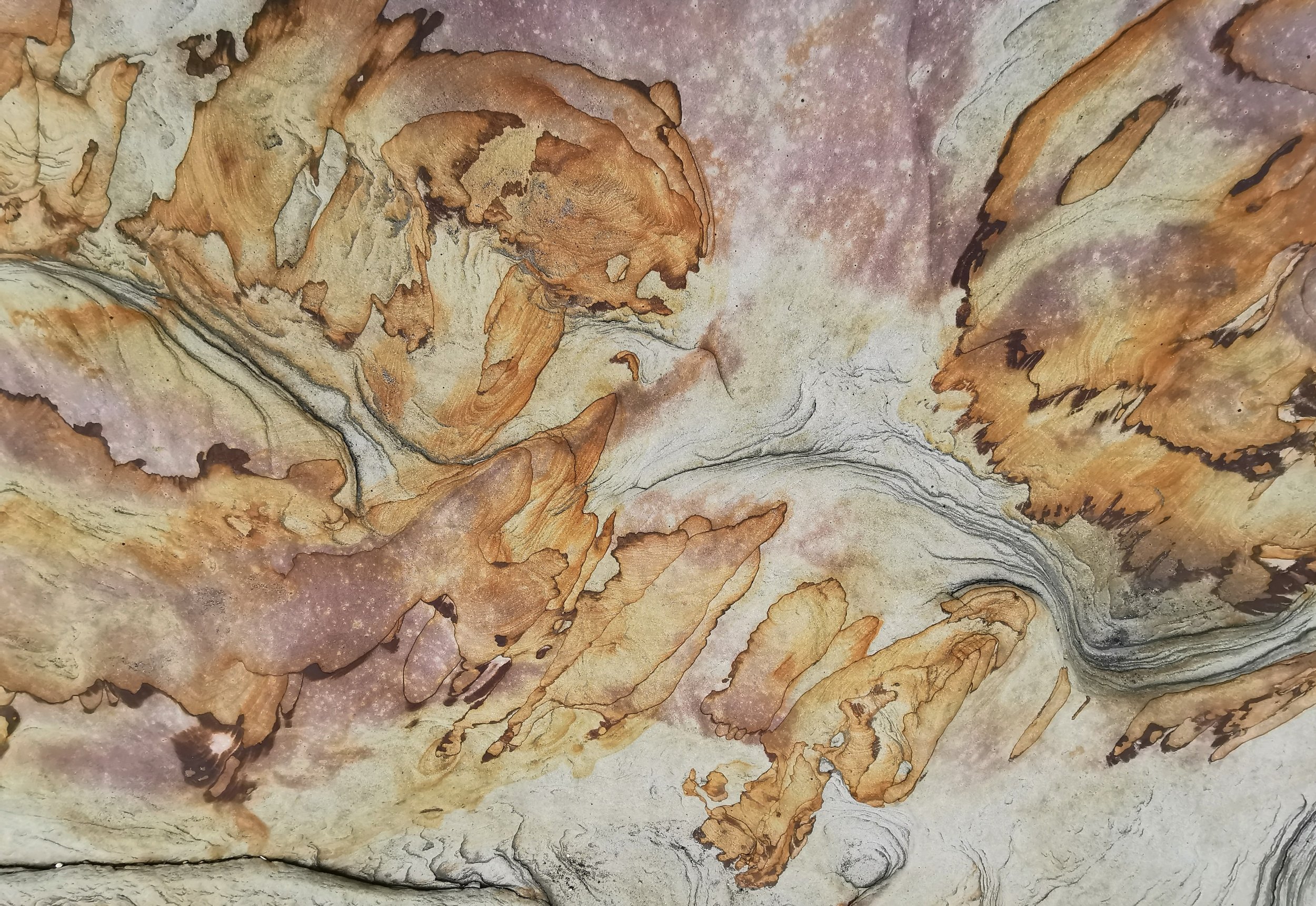

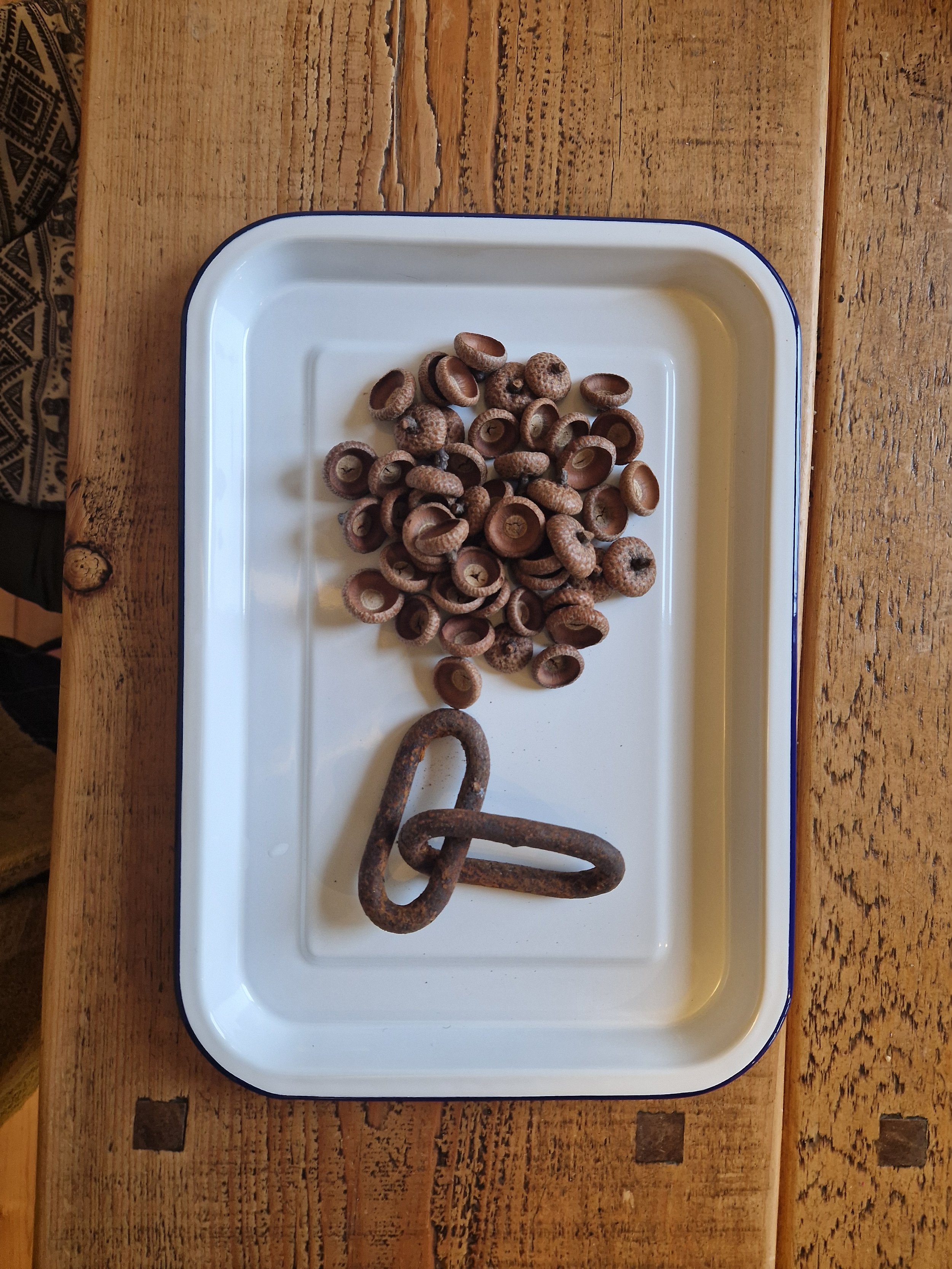

For years I’ve been consciously moving towards more sustainable practices in my art, often creating impermanent artworks that will eventually return to the landscape – for example by using foraged materials to create inks, dyes, pigments and photographic emulsions. Some days I’m foraging for scraps of metal washed up on the shores of our historical fishing villages to make botanical inks and dyes; other times I’m collecting remnants of scorched soil along St Monans salt pan shoreline or fragments of brick from Silverburn’s flax mill to grind into rich pigments. I find plants and seaweeds from which to create cordage, chlorophyll photography or green photography (where I substitute chemicals traditionally used in darkroom developing with various plant matter).

EXPLORING BIOMATERIALS

Experimenting with bioplastics made with seaweeds

Slow Photography Experiments with Algae | Cyanotypes on Agar

Below are a few images from my current research alongside a small part of our collection of foraged artefacts, old and new, found over the years exploring our varied coastline.